The Puzzling Resilience of Neoliberalism: Capitalism, Democracy, and Development in Latin America and Eastern Europe

Aldo Madariaga

Since the financial crisis, the continuity of neoliberalism has become a central focus of social science research. Focusing on Latin America’s and Eastern Europe’s more than three-decade history with neoliberal policymaking, Aldo Madariaga analyzes concrete policies, coalitions of actors, and political mechanisms to explain how neoliberalism survives.

Neoliberalism in the spotlight

Ever since the fall of Lehman Brothers in 2008, the future of neoliberal policies has been at the forefront of scholarly debates. The depth of the crisis in Wall Street and its many repercussions created expectations of a switch to more progressive policies. Nevertheless, neoliberalism has shown a surprising survival capacity. Scholars have termed this capacity to dominate over rival ideas, endure powerful political challenges, and survive through crises, “resilience.” Although a new anti-free market and protectionist rhetoric has emerged with the rise of populist politicians on the right and left, the consequences of this for the continued resilience of neoliberal policymaking are yet to be seen.

»In Latin America and Eastern Europe neoliberalism amounted to a complete restructuring of state–society relations with profound consequences for democratic processes, institution building, and policymaking.«

Latin America and Eastern Europe, two world regions with a history of more than three decades of neoliberal policymaking, provide a key focal point to analyze neoliberal resilience. Commentators have often noted the “laboratory conditions” under which neoliberalism was established in these regions – bloody military dictatorships in Latin America, the breakdown of communism in Eastern Europe – to explain neoliberalism's far-reaching consequences. In this sense, while in continental Europe neoliberalism has represented a more or less successful challenge to established ideas and institutions, in Latin America and Eastern Europe neoliberalism amounted to a complete restructuring of state–society relations with profound consequences for democratic processes, institution building, and policymaking.

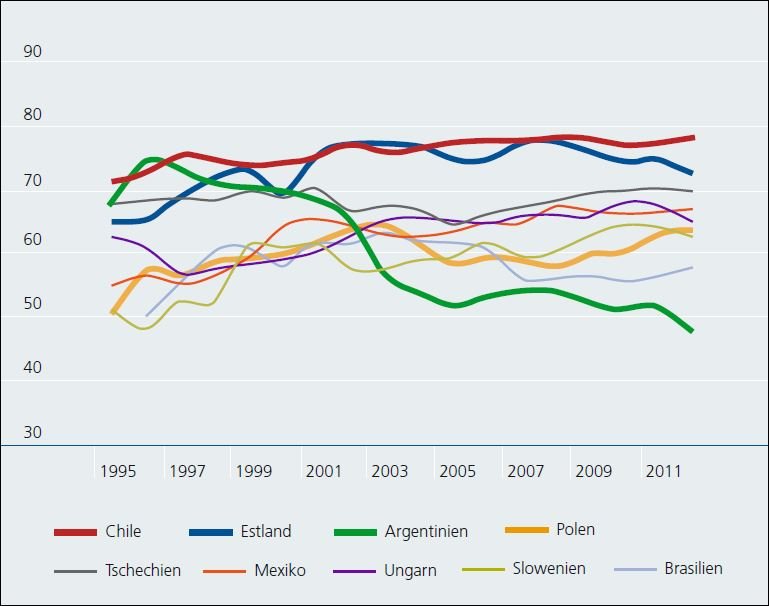

After years of adjustment, steep and repeated economic crises, disintegrating industrial and social structures, and growing unemployment and inequality, most countries slowed down the pace of reform or shifted their development models to other alternatives. However, a handful of countries maintained and reinforced neoliberalism over time (Fig. 1). To understand these different trajectories, a comparison of four countries where neoliberalism was adopted fervently, but had a different fate, is helpful: while it survived and was reproduced almost without challenge in Chile and Estonia, it was contested in Poland and defeated in Argentina.

Continuity and change in neoliberal policy regimes

Neoliberal resilience can be illustrated by the interplay between exchange rate regimes and industrial policy, two key policy domains in every development strategy. As a development strategy, neoliberalism considers markets to be the main allocation device in the economy and regards price stability as a crucial policy goal. Typical examples of neoliberal policy alternatives are fixed exchange rate regimes or their seeming opposite, freely floating regimes that limit state intervention and promote market forces. Another example is neutral industrial policies – including so-called “horizontal” policies – that limit state intervention to correcting market failures alone. Neoliberalism does not necessarily reduce state intervention; rather, it reduces the space for deliberate state action. Following this, one may say that a country departs from neoliberalism when policy alternatives allow discretionary government intervention favoring certain sectors over others. This occurs through explicit government management of the exchange rate or through targeted industrial policies.

Chile and Estonia show a record of neoliberal policy alternatives – with some changes within policy instruments especially in the case of Chile – while Poland and especially Argentina show a recurrent reliance on non-neoliberal policy alternatives such as managed exchange rate regimes and more interventionist industrial policies. In terms of societal support, neoliberal policy alternatives were pushed and defended by financial and exporting sectors and right wing (liberal) parties, while economic sectors demanding state protection, left-wing (socialist) parties, and labor have switched from opposition to conditional support. These coalitions of actors operated relatively similarly in the four countries, which means that power and interests alone have not been enough to maintain neoliberal policies over time.

Mechanisms of neoliberal resilience

The crucial difference between these countries lies in the operation of what can be called “mechanisms of neoliberal resilience.” Neoliberal coalitions have managed to remain powerful in Chile and Estonia thanks to concrete mechanisms institutionalizing their power, thereby controlling the trajectory of public policy. These mechanisms are: support creation among business elites through targeted privatization; blocking opposition from labor and left parties through liberalizing labor markets and establishing political institutions that bias representation; and constitutionalized monetarism, that is, strengthening the institutional constraints on changing existing neoliberal policies, especially when neoliberal policies are protected by norms of higher constitutional range, making them more difficult to change.

»Neoliberal coalitions have managed to remain powerful in Chile and Estonia thanks to concrete mechanisms institutionalizing their power, thereby controlling the trajectory of public policy.«

In Chile and Estonia, privatization served to create support, strengthening economic sectors whose expansion greatly benefitted from neoliberal policies. For example, in Chile companies with high stakes in the financial and export sectors had preferential access in acquiring state-owned companies due to their own economic activities or complementary ones. Similarly, in Estonia privatization had a clear bias benefiting multinationals. By contrast, a significant share of privatized assets in Argentina and Poland served to reinforce protectionist economic sectors, therefore providing power resources to oppose neoliberalism or extract concessions. This also implied that business support for neoliberalism there was less coherent and more prone to business resistance over time.

With respect to the opposition blockade, while all countries tried to reduce worker influence in decision-making, in Estonia and Chile workers lost the most through the institutionalization of collective bargaining structures at the company level and a sharp reduction in unionization rates. In Argentina, by contrast, workers managed to maintain collective bargaining structures at the sectoral level as well as relatively high unionization rates. While Poland is a story of declining labor power, its influence in policymaking has been closer to the Argentine story thanks to the maintenance of certain corporatist negotiation structures. Most significantly, unlike in Argentina and Poland, Chile and Estonia implemented electoral laws restricting the representation of the population that supported more progressive policies. In Chile, this was coupled with a set of non-elected veto points in and outside of Congress.

Neoliberal resilience in Chile appears to be closely connected with support creation. There, privatization strengthened the specific business segments that supported neoliberal policies and the Pinochet dictatorship. The difficulty that post-authoritarian center-left governments had in trying to break away from neoliberalism despite the rhetoric seems crucially affected by their inability to find a business support base. The Argentine trajectory of failed neoliberal projects, where the strength of alternative business segments was crucial in supporting departures from neoliberal orthodoxy, seems to confirm this.

In the case of Estonia, the opposition blockade was consequential. Unlike in Poland, where democratic governments failed to exclude post-socialist elites from access to power, in Estonia a persistent ethnic cleavage provided ground to block the supply of and demand for more active state policies. First, it permitted the establishment of exclusionary political institutions responsible for leaving between ten and forty percent of the population without voting rights. Second, it severely restricted the formation of parties representing the excluded population.

»The four countries have experienced thorough processes of constitutionalized monetarism.«

Finally, the four countries have experienced thorough processes of constitutionalized monetarism, in which the institutional constraints on changing existing neoliberal policies are strengthened, most notably constraining the ability of monetary authorities to engage in heterodox exchange rate policy through the institutionalization of independent and anti-inflationary central banks, and reducing governments' ability to support specific economic sectors through the implementation of strict fiscal spending rules. However, constitutionalized monetarism has depended crucially on the existing power balances. In Chile and Estonia, independent central banks and stringent fiscal rules have been backed by powerful neoliberal coalitions strengthened by the creation of support and opposition blockades.

Conversely, in Argentina constitutionalized monetarism has failed because there was no generalized political commitment to neoliberalism in the first place. The case of Poland, recurrent attempts to curb constitutionalized monetarism seem to confirm this. In fact, neoliberal and alternative coalitions have been in a constant fight for hegemony, neither of them being able to maintain an enduring advantage over the others.

The future of democratic capitalism

Based on these case studies, it could be argued that the resilience of neoliberalism has depended on the depletion of state resources, exclusionary politics, and the institutionalization of lower forms of democratic rule. State resources have been allocated with few checks to business actors committed to the maintenance of neoliberal policies and authoritarian policymaking styles. This means that national states may have forever given up control over crucial resources and industries to foreign interests or domestic capitalists more interested in extracting rents than advancing a country's development prospects.

Conversely, oppositions have been silenced through exclusionary electoral systems and liberal labor market institutions. This means that the ability of workers and those worse off to entice political turnover and policy change using electoral means or even protest is minimal. Finally, crucial policy decisions have been gradually placed outside the realm of democratic politics, depriving people of the policy instruments needed to meaningfully affect their lives.

»The resilience of neoliberalism has depended on the depletion of state resources, exclusionary politics, and the institutionalization of lower forms of democratic rule.«

The comparative analysis shows that these are global rather than idiosyncratic mechanisms of neoliberal resilience. In this spirit, they cast doubt on the future of democratic capitalism well beyond the periphery of the capitalist world.