Informal Racial Exclusion and Local Socioeconomic Outcomes: The Colombian Case of the Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Irina Rosa España Eljaiek

The social sciences have developed an extensive literature on the effects of the informal exclusionary institutions of racial exclusion on local socioeconomic outcomes. However, less attention has been paid to the specification of the theoretical mechanisms that explain how the effects take place via the dynamics of local social actors in the face of exclusion.

Colombia is an ideal case study to analyze both the effects of informal racial exclusion and how these effects take place. As a former Spanish colony, this country experienced formal rules to exclude the non-white population and favor white Spaniards during the colonial period. Independence from Spain eliminated these formal exclusionary rules. However, historiography shows that informal racial exclusion endured, especially during the republican period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

This informal racial exclusion took regional dimensions, affecting local socioeconomic performance. The literature describes that Colombia presents a phenomenon of historical regionalization of the race. This phenomenon consists of the historical persistence of colonial racial patterns of settlements. That means that a population of white-Spanish origin tended to settle in the Andean-central regions of the country, while the coastal areas are mainly inhabited by the descendants of African and native populations. Hence, in a context where the exclusion of the non-white population informally prevails, in non-white regions racism and exclusion may led to lower socioeconomic performance, especially in regions with a greater Afro-descendant component.

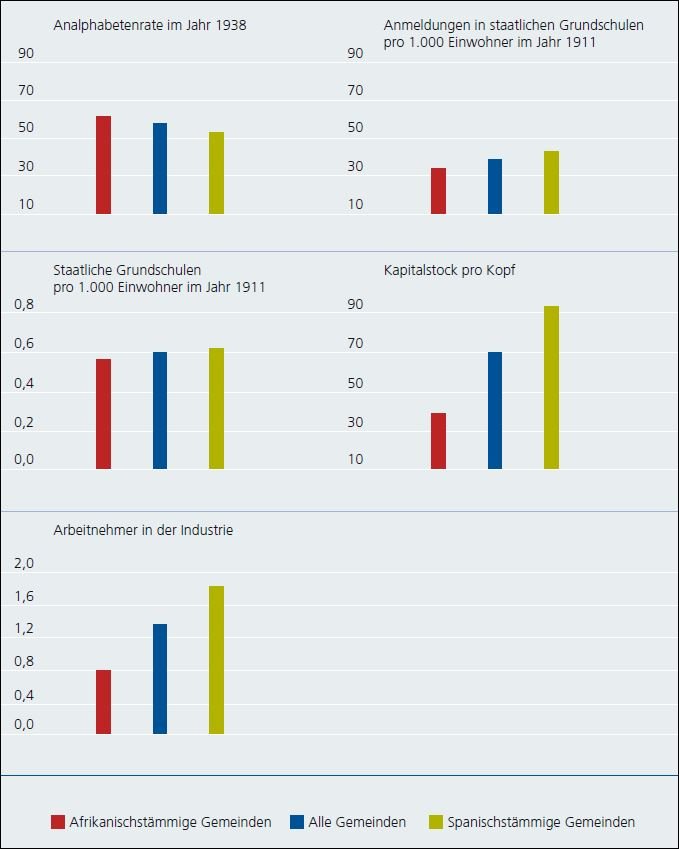

Sources: census of the population, FIC, MIP (1911).

Figure 1 illustrates regional racial disparities on different indicators of socioeconomic performance in Colombia during late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

»Implicit racism may have a negative impact on local socioeconomic development.«

It becomes obvious that more Afro-descendant municipalities present lower indicators associated with socioeconomic development. For instance, more Afro-descendant municipalities show lower enrollment rates in primary schools, lower numbers of schools, and higher rates of illiteracy. Additionally, Afro-descendant municipalities have lower rates of per capita industrial capital and establishments. These results confirm that more Afro-descendant regions present a lower socioeconomic performance, suggesting that implicit racism may have a negative impact on local socioeconomic development.

Although the data suggest a potential negative correlation between racial exclusion and local socioeconomic development, this information cannot capture the causal mechanism that explains how racism affects socioeconomic outcomes at the local level. In other words, it cannot fully account for the dynamics between exclusion and local social actors that result in the lower performance of Afro-descendant regions.

A case study analysis is precisely what is needed to capture this causal connection. The region of Chocó, located in the northwest of the country, is an ideal region for a detailed analysis. Chocó is a historically excluded region with the greatest percentage of population of Afro-descent in the country and low socioeconomic outcomes, particularly low provision of public goods.

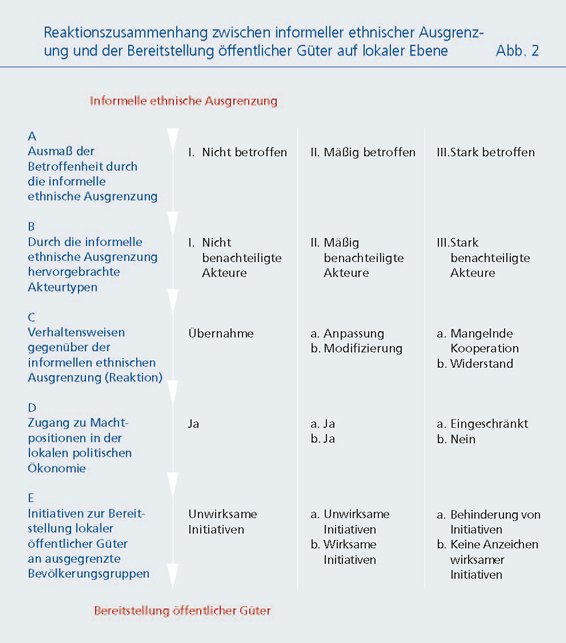

The analysis shows that there is a mechanism of reaction (Figure 2) between the informal institution of racial exclusion and the provision of local public goods. The mechanism shows that racial exclusion shapes three local actors: the “non-aggrieved,” “mid-aggrieved,” and “aggrieved.” These actors react to the exclusionary institution with five different types of behavior: “adoption,” “adaptation,” “non-cooperation,” {revision,” and “contestation” of the informal institution of racial exclusion. These behaviors are forms of either altering or reinforcing the informal exclusionary institution. In turn, these alterations and reinforcements affect the provision of local public goods when actors and their specific types of behavior are related to the local political economy of public good provision. Hence, the final link indicates that behaviors such as adoption, adaptation, and non-cooperation facilitate low public good provision. In contrast, behaviors such as revision and contestation tend to facilitate effective initiatives for a better provision of local public goods.

Non-aggrieved actors, adoption of exclusion, and local performance

Local non-aggrieved actors face no level of being affected by the informal exclusionary institution because they do not represent the socio-racial characteristics related to this institution. Racial exclusion accommodates them in an advantageous position, controlling access to resources. These actors are frequently in positions of power in the local political economy of public good provision. Therefore, they favor adoption of the exclusionary institution as their specific behavior, which leads to ineffective initiatives for the provision of local public goods for the excluded population.

The predominant behavior of the local white minority in Chocó corresponds with that impression, as these elites control access to resources. To maintain their power, they reproduce the informal institution of racial exclusion by implicitly “adopting” white values as the ideal for the Chocoana society. In turn, when they are in charge of the local political economy, their behavior of adoption is related to omission, negligence, and/or corruption in the provision of public goods oriented toward the majority of poor Afro-descendant Chocoanos.

Mid-aggrieved actors, adaptations, revisions, and local performance

In contrast to the non-aggrieved, mid-aggrieved actors have a moderate level of being affected by the exclusionary institution. They have some socio-racial characteristics related to the exclusionary institution, but their level of affectation differs extensively from that of a typical aggrieved actor. The main reason for that is that mid-aggrieved actors either have access to resources or the attributes related to exclusionary institutions are relatively dissimulated. Thus, these elements minimize their disadvantage.

Mid-aggrieved actors show two main types of behavior: adaptation and revision. The first behavior, adaptation, is visible in regular practices that implicitly reproduce racial exclusion. Moreover, when adapted mid-aggrieved actors hold positions in the local political economy of public good provision, adaptation is observable in tacit practices that lead to ineffective initiatives for the provision of public goods for the excluded population. For example, this was the case for the new mulato Chocoana elite during the mid-twentieth century.

The mulato Chocoana elite are a minority of individuals with Afro-descendant heritage. They faced the effects of the implicit exclusionary institution; however, they were finally able to improve their social standing with access to resources like wealth and education. With a better social standing, they adapted the exclusionary institution, reproducing the prevailing white values. More important, though, when those actors were in positions relevant for the local political economy of public good provision, adaptation had the connotation of tacit exclusionary public policies. For example, they supported tacit white immigration, acted in a negligent manner, or allocated scarce public resources to profligate investments, going against the welfare of the local Afro-descendant majority.

»In a better social standing, adapted mid-aggrieved actors reproduce the exclusionary institution.«

A second type of mid-aggrieved actors tries to revise the exclusionary institution. This behavior leads to effective initiatives for the provision of public goods that are targeted at the main part of the excluded population. Similar to the adapted mid-aggrieved actors, the revisers share some attributes of their Afro-descendant heritage. They were also able to improve their social standing through money or education. Moreover, many of them joined the local public administration of Chocó. Nevertheless, and in contrast to the adapted mid-aggrieved actors, this category of mid-aggrieved actors revised exclusionary policies like implicit racial segregation in education. This was relevant in the path to a better provision of public goods, like more schools for the poor majority of Afro-descendant Chocoanos.

Aggrieved actors, non-cooperation, contestations, and local performance

Aggrieved actors are the majority in Chocó and are highly affected by racial exclusion. Thus, they have socio-racial characteristics associated with the exclusionary institution. Moreover, they have relatively low access to physical or human resources. Consequently, their level of being affected is high. Aggrieved actors generally show two behaviors: They behave with non-cooperative actions or contest the exclusionary institution.

Behaviors like non-cooperation reproduce the exclusionary institution. Non-cooperation means actions related to rivalries, antagonisms, or egoisms, that is, a lack of cooperation among the similarly aggrieved population. In turn, these behaviors of reproduction block initiatives that could lead to a better provision of public good. This was the circumstance many Chocoanos found themselves in, for instance, competed with each other, blocking initiatives for the provision of public goods in national and local spaces.

However, aggrieved actors also contest the exclusionary institution in the form of protests, demands, and/or complaints against tacit exclusionary policies or actors. These contestations rarely improve the provision of public goods, though, because the access of aggrieved actors to resources is highly limited. They are not capable of influencing the local political economy of public goods in meaningful ways. Nevertheless, these protests set a clear precedent for future revisions, and over time, some of such demands have been taken up by revisionist mid-aggrieved actors.

»The protests of aggrieved actors set a clear precedent for future revisions, and over time, some of the demands were readdressed by revisionist mid-aggrieved actors.«

In summary, the informal institution of racial exclusion explains local differences in socioeconomic outcomes in Colombia. Moreover, the dynamics of local actors in the face of exclusion are important in such as differences. Unquestionably, further work would shed light on topics such as a systematic explanation of how actors in the mechanism opt for the expected behavior rather than another one. However, the findings illustrate issues that are almost always opaque in works that study the effects of exclusionary institutions on local socioeconomic development.